Road, Highway & Railway Drainage Design Guide: Open Channels (Types, Slopes, Dimensions, and Key Formulas)

1 February 2026Table of Contents

Road, Highway & Railway Drainage Design Guide: Open Channels (Types, Slopes, Dimensions, and Key Formulas)

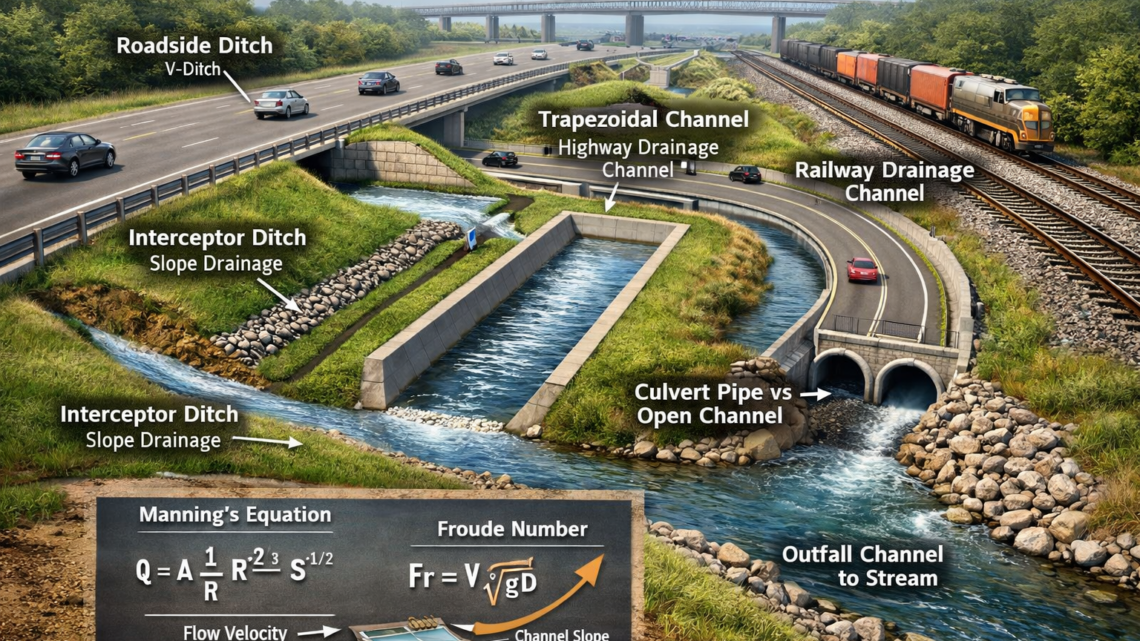

Open Channels in Transportation Drainage

In roads, highways, and railways drainage, an open channel is any conveyance where water flows with a free surface exposed to the atmosphere. Typical examples in transportation corridors include roadside ditches, median channels, interceptor drains along cut slopes, toe drains, and outfall channels that safely carry runoff to culverts, bridges, or receiving waterways.

Open channels are used because they’re easy to inspect, can handle sediment and debris, and are often more economical than large closed conduits—especially over long linear corridors.

1) Types of Open Channels Used in Roads, Highways, and Railways

A) By function in a corridor

-

Roadside ditch (longitudinal ditch): runs parallel to the road/track to collect runoff from pavement and side slopes.

-

Intercepting ditch (catchwater drain): placed upslope to prevent hillside runoff from reaching the roadway/rail formation.

-

Median channel: used in wide medians to convey runoff toward cross-drainage points.

-

Outfall channel: carries concentrated discharge from culverts/outlets to a natural channel, with erosion protection.

-

Side slope/toe drain (rail or road embankment): protects embankment stability by controlling surface water and reducing erosion at the toe.

B) By cross-section shape (most common in transport)

-

Triangular (V-ditch): very common for roads because it’s simple and fits narrow right-of-way; good for small to moderate flows.

-

Trapezoidal ditch: common where larger capacity is needed and maintenance access is required; more stable than a deep V-ditch.

-

Rectangular channel: often concrete-lined in constrained areas (urban roads, underpasses, stations, retaining walls).

-

Compound sections: used for floodways and large outfalls (main channel + benches) to handle extreme events safely.

C) By lining (chosen based on velocity, durability, and maintenance)

-

Unlined (earth/grass): low cost, good for mild slopes and manageable velocities; requires vegetation management.

-

Riprap / rock lining: common at outfalls and steep sections; strong erosion resistance.

-

Concrete lining: used where space is limited, velocities are high, or maintenance must be minimized.

-

Gabions / geotextile systems: used where settlement may occur or flexible protection is needed.

2) Grades and Slopes in Transportation Drainage

In channel design, grade is the bed slope S0 (m/m or %). In road and railway corridors, slope selection is often constrained by:

-

roadway/track longitudinal profile,

-

available right-of-way,

-

tie-in elevations at culverts and outfalls,

-

need to avoid erosion and protect embankments.

Key transportation drainage reality

Roadside ditches often follow the corridor grade—so you control erosion with:

-

lining upgrades (grass → riprap → concrete),

-

check dams or drop structures,

-

energy dissipators at outlets,

-

flatter cross-sections (wider/shallower) where possible.

3) Common Dimensions (Depth, Width, Side Slopes) for Road/Rail Ditches

There is no single “maximum” depth/width because design depends on discharge Q, safety, soil stability, and right-of-way. However, typical practical ranges for transportation drainage are:

A) Roadside V-ditches (common on highways)

-

Depth: ~0.3 to 1.0 m

-

Top width: often ~1.0 to 3.0 m (depends on side slopes and depth)

-

Side slopes: typically 3H:1V or flatter for safety and stability

B) Trapezoidal ditches (higher capacity + easier maintenance)

-

Depth: ~0.6 to 2.0 m

-

Bottom width: ~0.5 to 3.0 m

-

Side slopes: commonly 2H:1V to 4H:1V (flatter near high-speed roads)

C) Railway longitudinal drains (common along formation and cut sections)

-

Often shallower and well-defined to protect ballast/subgrade:

-

Depth: ~0.4 to 1.5 m

-

Bottom width: ~0.4 to 2.0 m

-

Side slopes depend on soil and maintenance access, often 2H:1V to 3H:1V

-

Practical limits that often govern ditch size

-

Safety clear zone: deep/steep ditches increase crash severity near highways.

-

Maintenance access: equipment needs room; trapezoids are often preferred.

-

Erosion control: unlined sections must stay within permissible velocity/shear.

-

Right-of-way constraints: urban sections may force concrete channels or pipes.

4) When Do We Use Open Channels in Road/Highway/Rail Projects?

Open channels are used when:

-

you need longitudinal drainage over long distances,

-

you want a visible, inspectable system (blockages are easier to detect),

-

you expect sediment/debris (common in cut slopes and unpaved areas),

-

the corridor has enough space for a ditch section,

-

you want lower cost than large storm pipes for the same capacity,

-

you need a robust system that can safely convey extreme storm overflow.

5) Why Channels Are Often Preferable to Culverts or Pipes (in Corridors)

Advantages of open channels

-

Cost-effective for long runs beside roads/railways (pipes are expensive over kilometers).

-

Easier inspection: water, erosion, and blockages are visible.

-

Better sediment/debris tolerance: ditches can be cleaned mechanically.

-

Reduced hidden failures: pipes can clog or collapse without obvious warning.

-

Flexible upgrades: you can widen/line a ditch more easily than replacing a pipe.

When culverts/pipes are still necessary

-

Crossing under the road/rail (cross drainage),

-

Dense urban constraints,

-

Safety/aesthetics,

-

When you must keep water out of the clear zone (site-specific).

6) Stormwater vs Open Channel in Transportation Drainage

-

Stormwater = rainfall runoff and the full management system (inlets, gutters, ditches, pipes, culverts, detention, outfalls).

-

Open channel = a conveyance type that may carry stormwater.

So in transportation projects:

-

Stormwater can flow via gutter → inlet → pipe, or shoulder → ditch → culvert/outfall.

-

An open channel is often the primary longitudinal collector, while culverts are used for crossings and outlets.

7) Core Formulas Used for Open Channel Design (Most Common)

A) Continuity (flow rate)

Q=A V

Where:

-

Q discharge (m³/s)

-

A flow area (m²)

-

V mean velocity (m/s)

B) Manning’s Equation (the most used for roadside/rail ditches)

V=1nR2/3S1/2⇒Q=A⋅1nR2/3S1/2

-

n Manning roughness (depends on lining)

-

R=A/P hydraulic radius

-

S energy slope (often approximated as bed slope for uniform flow)

C) Hydraulic radius

R=AP

-

P wetted perimeter

D) Froude number (checks subcritical/supercritical flow)

Fr=VgDwhereD=AT

-

T top width of flow

-

Fr<1 subcritical, Fr>1 supercritical

E) Specific energy (useful for transitions/outfalls)

E=y+V22g

-

y flow depth

F) Critical depth (rectangular channel, helpful near controls)

yc=(Q2gb2)1/3

-

b channel width

G) Boundary shear stress (tractive force method; erosion/lining check)

τ=γRS

-

γ unit weight of water (~9810 N/m³)

-

compare τ to permissible shear for soil/lining

8) Practical Design Workflow for Road/Highway/Rail Open Channels

-

Estimate design flow Q from catchment area and storm criteria (road/rail drainage design storm).

-

Choose channel location and function (roadside ditch, intercepting drain, outfall).

-

Select a cross-section (V or trapezoid is common).

-

Use available profile to set bed slope S0 (or plan drop structures if steep).

-

Pick roughness n based on lining (earth/grass/riprap/concrete).

-

Size the channel using Manning to satisfy:

-

capacity (carry Q)

-

velocity and/or shear limits (avoid erosion)

-

freeboard and overtopping considerations

-

-

Detail inlets, culverts, transitions, and outlet protection (riprap aprons, stilling basins, check dams).

-

Add maintenance and safety features:

-

flatter side slopes near high-speed roads,

-

clear zone considerations,

-

access points for cleaning.

-